We are in the time between winter and spring. We have just passed ‘Imbolc’ on February 1st and 2nd , originally a Celtic fire festival to celebrate the forthcoming spring, the return of the light and to honour the goddess / Saint Brigid.

According to Irish folklorist and academic Ó Catháin in his book ‘The Festival of Brigid: Celtic Goddess and Holy Woman’, the folklore associated with Brigid shares links with Shamanic practices of bear cults over 4,000 years ago. Critics find his connections are somewhat tenuous, as he doesn’t present enough evidence to support his theories. I have yet to acquire the book to share my thoughts on the matter, but looking forward to reading about his theories on fire symbolism and connections with bees, oystercatchers, cranes, shellfish, acorns and stones!

It sounds like a wonderful cabinet of curiosities!

However, there are connections that give his theory some gravitas, that being the coming of spring.

Brigid represents motherhood and fertility, she is nurturing and protective, she is the light and the spring, a symbol of renewal and positivity. These traits are shared by the Celtic great mother bear goddess, known as Artio or Dea Artio, (or any female mother bear at this time of year) who wakes from her winter hibernation in her dark cave, gives birth to cubs and protects them until they are strong enough to go out into the light, the light of Brigid’s ever burning flame. Emerging from the darkness, in some ways the bear’s journey mirrors the shaman’s path—a descent into the hidden realms of the spirit world to return with the gifts of wisdom and enlightenment.

Evidence of Celtic and Gallo Roman bear worship comes to light through ancient carvings and funerary remains found in various locations around the Celtic world like these 5th century BCE sandstone bear statues found at Armagh, and the later Gallo Roman bronze statuette found at Muri bei Bern, Switzerland of the bear goddess standing facing a seated woman with a basket of fruit and a plate. Perhaps she is about to feed the bear, as a form of worship, whereas it’s possible the fruit signifies abundance, another indicator of spring.

In a churchyard in Dacre, Cumberland, stand four stone bears, supposedly Medieval, although it’s debatable, they could be a lot older possibly pre Roman.

In a church in Brompton a discovery was made during the 19th Century of these beautiful bear carvings on the stone hogbacks, believed to be 10th century CE.

In Welwyn Garden City grave, the late Bronze Age remains included ashes of a male human buried with silver cups and pottery vessels (suggesting he was of high status) as well as 6 bear phalanges. Experts indicate that a bear pelt was wrapped around the body before cremation, not only to protect his remains but also to spiritually protect him in his journey to the afterlife or otherworld.

But what about Dartmoor? Were there brown bears on Dartmoor?

It’s very possible. During the Bronze and Iron Ages, Dartmoor would have had more trees in the valley areas than today. Caves would’ve been similar as they are today, set within the rocks and tors, and the climate shifted to a cooler wetter one after the warmer Bronze Age. All perfect conditions for brown bears.

In 2011 archeologists found Bronze Age remains in a cist on Whitehorse hill on Dartmoor. Among them were the cremated ashes of a young person, a basket of jewellery and a bear pelt that covered the remains and wasn’t burnt. The quality of the necklace suggested again that the person was a female of high status, possibly a Celtic princess.

It’s possible these bear pelts were traded from overseas, but further evidence suggests that they were living here in the UK probably from before the ice age right through to around 500CE, when they became extinct due to hunting.

But here’s food for thought, why was the bear pelt wrapped around the body ‘before’ cremation took place at Welwyn but only placed with the ashes ‘after’ cremation at the Whitehorse hill site? Was this a difference between a male and a female burial? Or was it a geographical difference in funerary rites? Or was it not actually wrapped around the man after death but being worn as a garment when he died? If that was the case then why wasn’t the woman wearing hers, did she die in fewer clothes, at night maybe whilst sleeping under her bear pelt? Or did the pelt belong to another, maybe a lover or her father?

Perhaps they believed that by keeping the bear pelt in tact for this princess there would be even more chance of enabling a peaceful transition to the otherworld.

Which brings us back to the start of this post and the significance of the Great Mother Bear goddess.

But I have another burning question, (!!) what happened to the other four bear phalanges at Welwyn?

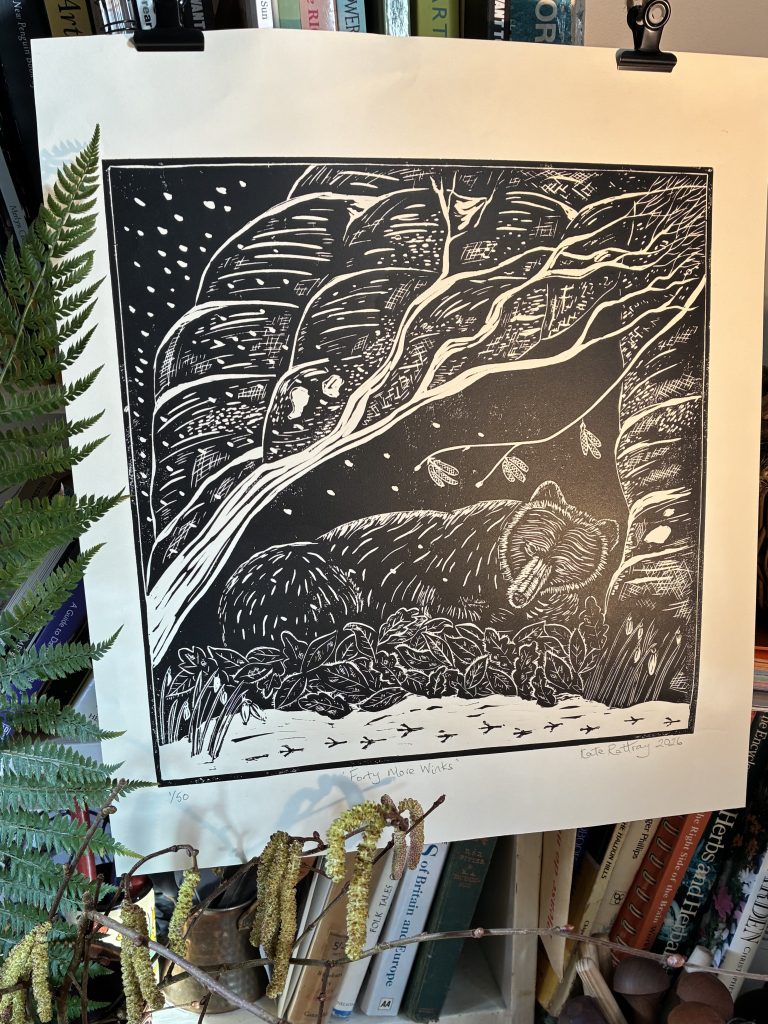

Here is my new print…